Eleanor dragged a chair underneath the palm tree farthest away from the pool. She started a crossword puzzle, but after a few minutes, the pool seemed to be calling to her. “Eleanor, come swim in me, please.” She walked to the edge, feeling in her tank suit that she was naked in front of strangers. A sensation she hadn’t experienced in decades. It wasn’t entirely bad. Even though each hair on her head was silver, she still had a nice rack. She dipped one foot in, then the other. She sat down and lowered herself into the water. It was at once an icy shock and a warm embrace. She lowered herself in even more, until her whole head was wet.

“Daniel, I’m going to eat you up!”

A red-haired woman stood a few feet away hugging a little boy, who was probably no more than four. He screamed with joy. The woman play-bit his chubby cheeks. Eleanor swam away. Even though her face was wet, she didn’t want anyone to notice she was crying.

Daniel reminded Eleanor of her son, Frank, who’d wanted to go to the pool every day when he was little. In the summers they’d lived with shiny splotches of aloe vera on their pink shoulders and cheeks. Those days were the best because Frank hadn’t put a pill in his mouth yet. Frank had come home for Sam’s funeral, taken one of his suits and a pair of cufflinks, and then disappeared. One night Eleanor had seen Frank sitting at the entrance to the highway, holding up a sign that said: “Out of Work, Please Spare Some $ For A Starving Artist!” He wore Sam’s suit and she’d wanted to stop, but seeing his bleary eyes and his skeletal frame had made her cry harder at the funeral than her own husband’s death. She drove on.

The red-haired woman was there with Daniel every day. Eleanor soon learned their routine. The mother would play with him for a bit, then she’d go to her chair and text, or take selfies. Some days she had another woman with her who vaped even though there was a no smoking policy. Daniel’s mother hardly looked at him after their initial playing. He mostly set on the steps or clung to the sides. Sometimes he played with other children.

The day that Daniel didn’t come up for air, Eleanor was drinking a Diet Coke and finishing up a crossword puzzle. She’d had a headache all morning and looking at the bright light bouncing off of the pool made the headache worse. It was the first day she hadn’t been watching Daniel. His mother’s friend wasn’t there and she’d been more attentive to her son, which made Eleanor feel better about not looking.

A scream made her drop her book. Eleanor yanked off her sunglasses. A crowd was starting to form. Eleanor ran over and pushed through the people. Daniel’s tiny body was on the ground. His eyes were shut. Daniel’s mother knelt beside him.

“Who knows CPR? Where’s the lifeguard?” someone shouted.

There was only one lifeguard on duty and Wednesdays it was Hunter, who spent most of his time chatting up the girl who ran the snack bar.

Eleanor knelt beside Daniel. She put her hands on his chest. She pumped. She blew into his mouth. Over and over. Daniel’s mother wailed. In her mind, Eleanor was back in Frank’s bedroom, the night she’d gone up to drop off his clean laundry. She’d knocked, not wanting to disturb him if he was deep in his drawing, but then she rationalized it would only take a second to put away his underwear. She opened the door to find him on his back on the floor. His cheeks were blue.

“If you didn’t get there when you did, he wouldn’t have made it,” the EMT told her.

Sam had been incredulous. “I didn’t know you knew CPR.”

But of course she did. Being a mother was a serious job.

After a minute Daniel’s eyes fluttered open. He spit out bubbles of water. Then he began to cry. He reached his arms up and Eleanor pulled him to her chest, the way she’d done with Frank.

Eleanor felt a tap on her shoulder and turned to find Daniel’s mother. Eleanor handed Daniel to her, and the two clung to each other. Eleanor looked up at the eyes staring down at them.

Hunter burst through, pushing his long bangs off his forehead. “Shit. Is everyone okay?”

“Look who finally decided to show up,” a woman said.

Daniel’s mother, trembling, grabbed Eleanor’s arm.

“I don’t know what I would’ve done,” she said. “Thank you.”

Eleanor could tell by the way the mother wouldn’t look her in the eye that there was a lot riding on what Eleanor said next. She had the power to wipe this woman out with her words.

“It’s the hardest job on the planet,” Eleanor whispered. “We do what we can.”

Daniel’s mother said: “I’m Annie.”

“Eleanor.”

“My son is Daniel.”

“Nice to meet you both.”

“Is she the lifeguard?” a little girl asked, pointing at Eleanor. A few people laughed, a welcome break to the tension of the moment. It was a wild idea—Eleanor being a lifeguard at 68. But she could do anything if she put her mind to it. Isn’t that what she always told Frank, when he was learning to ride a bike, apply to colleges? He never would’ve gone to Stanford if she didn’t encourage him. Why was she so different?

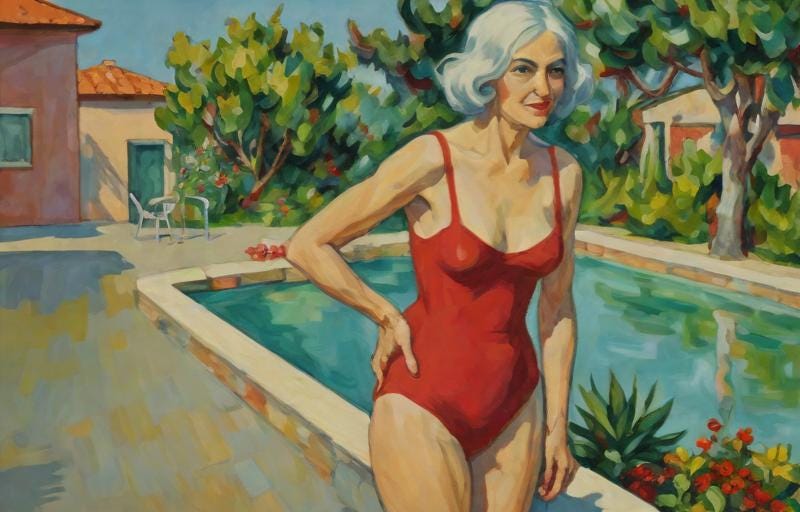

Eleanor waved goodbye to the people at the pool, who she was now gleeful to see regarded her with interest instead of ambivalence. She had a duty to perform again. She had to keep everyone safe. Maybe she’d buy a whistle. A red swimsuit. Sam always said she looked sexiest in red.

Jennifer Dickinson’s fiction has appeared in Beloit Fiction Journal, The Florida Review, Blackbird, Juked, JMMW, Maudlin House, Isele Magazine, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of a Hedgebrook residency and a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund. She is a book coach and lives in Los Angeles.

Why We Chose This Story: To learn why “The Lifeguard” was selected for publication, read our editorial notes in “Why We Chose It.”