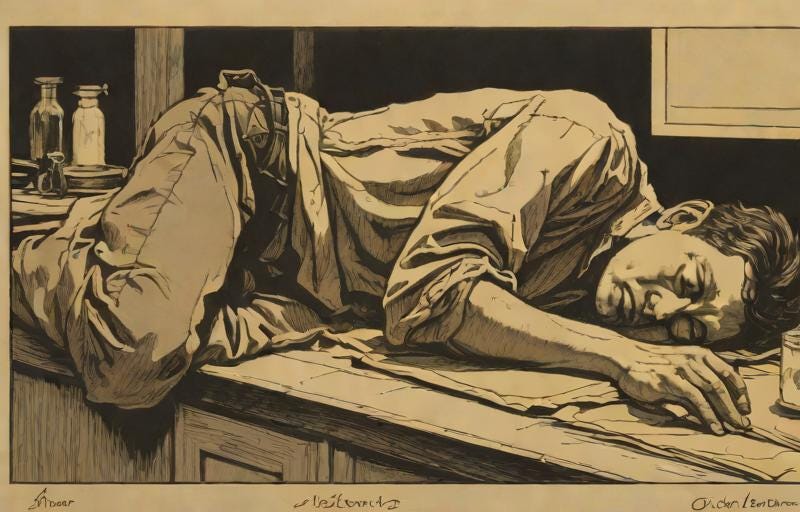

After the divorce I took to scrubbing the kitchen counters, so much so they had become smooth and soft, better than my own bed it seemed. I decided to spend the night, just to see what it was like. I squeezed the knife block, the food processor, the microwave and the toaster right into the corner, leaving plenty of room for me to stretch out. I grabbed some blankets and a pillow and climbed up, flicking the light switch with my toe.

The longer I stayed, the more I noticed. The smells deepening: the bananas, the apples in their basket hanging above my head, the faint smell of all the cleansers. I could feel the house settle, the refrigerator hum. The moon shone through the window, and more, I could see the tree branches slowly sway. I knew that when I’d fall asleep instead of the usual reenactments of all the things I’d done wrong, I was going to have amazing dreams, the sort where when you open your mouth nothing but poems pour out, the sort where you even get to remember some of those poems. And one of those poems would be so good maybe, maybe. I closed my eyes.

Instead of sleep I felt a little nip. I ignored it, thinking it was probably just a pulled muscle from all the cleaning. But then I got it again, along with a tiny “Hey!” in my ear. I opened my eyes: I was surrounded by mice.

“You can’t sleep here,” one of them said.

“Why not?” I asked. “It’s my house: I can sleep anywhere I want to.”

That’s when they showed me their title. It was written in mouse, and very small. “No court would acknowledge it,” I told them.

“But it’s in your handwriting,” another mouse declared.

“I don’t know mouse,” I said.

“You’re speaking it right now,” the first mouse piped furiously. “You even know how to lie in it. No wonder your wife left you.”

The kitchen filled with more and more mice, increasingly angry to see me lying on the kitchen counter instead of in the bedroom where I belonged.

“Countersleeper,” they all cried. “Liar and leasebreaker!”

“No,” cried yet another mouse, piebald with brown and white fur. “This is an opportunity. If that jerk won’t follow the rules, then why should we? Let us go where we like, any time we like, and instead of cowering underneath the dishwasher we can sleep anywhere, like in his dresser, snug in his underwear and socks. We can throw parties at three in the afternoon on weekdays!”

“And we’ll no longer have to sneak around whenever we want to do it,” asserted another five all at once.

“That’s fine by me,” I said. “But can I still go to sleep up here?” The counter felt so good on my back, and I was so sleepy.

They huddled. The kitchen filled with smoke; the discussion that fierce.

“That depends,” one of them at last said, waving the title in front of my eye. “Are laws dreams, or are dreams laws?”

But I was already asleep, and in my dream I was writing furiously, on a very small piece of paper, everything I thought was in my heart. But instead of poetry all I seemed able to write were rules, a settlement.

So when I fitfully woke up with all the mice staring at me, I grabbed my blanket and pillow, and went back upstairs to my soft and lonesome bed.

Hugh Behm-Steinberg’s prose can be found in X-Ray, The Pinch, Invisible City, Heavy Feather Review and The Offing. His short story "Taylor Swift" won the Barthelme Prize from Gulf Coast,and his story "Goodwill" was picked as one of the Wigleaf Top Fifty Very Short Fictions. A collection of prose poems and microfiction, Animal Children, was published by Nomadic/Black Lawrence Press. He teaches writing and literature at California College of the Arts.