A Good Feeling

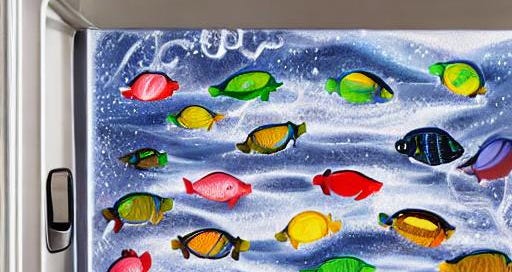

I can’t stop thinking about refrigerators.

Things you don’t think about until they die: squirrels in the attic, ex-lovers, refrigerators.

Mine died on a Wednesday in April (the refrigerator, not the ex-lover). Had it been the only complication in my life at that moment, I might have coped better.

Things that can trigger a descent into depress…