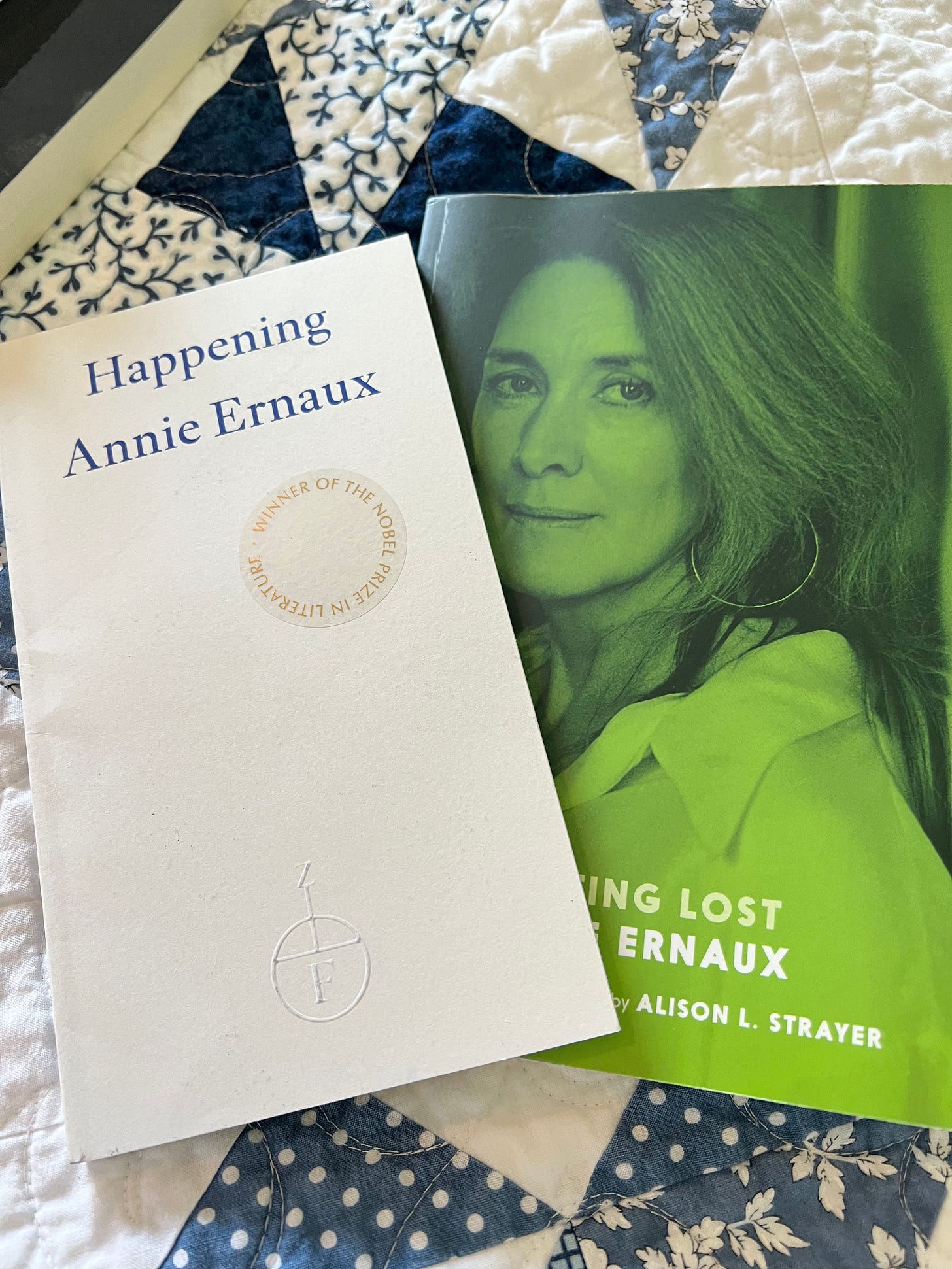

During the last few weeks, I’ve spent some time with Getting Lost, by Annie Ernaux, who won the 2022 Nobel Prize for Literature. Ernaux, who lives in France, received the prize “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.” She delivered her Nobel Prize lecture on Dec. 7th. You can watch it here.

“And I conceived of writing as nothing less than the possibility of transfiguring reality,” she says in that lecture. The reality she set out to transfigure was one of class, her sense of herself as belonging to a tormented class of people.

I proudly and naively believed that writing books, becoming a writer, as the last in a line of landless labourers, factory workers and shopkeepers, people despised for their manners, their accent, their lack of education, would be enough to redress the social injustice linked to social class at birth.

Getting Lost was first published in French in 2001. The English translation by Alison L. Strayer was published by Seven Stories Press in 2022.

The book is the journal of Ernaux’s year-long affair with a Russian diplomat during the early days of Perestroika. In it, she returns often to the subject of writing, in particular the writing of the journal:

This journal should have two columns, one for immediate writing, the other for interpretation a few weeks later. That would be a wide column because I could write several interpretations.

As someone who keeps notebooks but doesn’t journal per se, I appreciate this. When I’m going back to my notebooks to transcribe them onto my computer—which I’ve been doing for the past few months for The Wandering Writer—I often make additions and footnotes as I transcribe. In this way, the thing that makes it onto the typed page is a conversation between the person who wrote the notebook, months or years ago, and the person transcribing it—the same person, of course, but with the perspective of time and distance. By the time I publish a notebook entry, it covers at least two times and places, sometimes more. The interpretation lives alongside the original notebook entry.

One of the most beguiling aspects of Getting Lost is the immediacy she mentions here. Of course, she is a writer, so no doubt she revised carefully before sending this journal out into the world as a book. Yet she was able to maintain that sense of immediacy, the sense that we are reading the thoughts and feelings she had at a particular moment in time, exactly as she wrote them down. In truth, of course, all writing is artifice—whether revised or not. We revise the story as we put it down on the page, we cannot help but filter it and treat the self as a character once or twice removed. Ernaux, who seems fully aware throughout the writing of the journal that a book will come out of this affair, no doubt keeps the reader at a distance in some sense without making us feel that we are at a distance.

The book is filled with insecurity and self-doubt. One of the issues Ernaux takes with herself is her complete abandonment of writing during the year of the affair. Ultimately, the affair led to this book, but she did not get to this point without a lot of emotional and intellectual pain:

A sense of my own mediocrity, a general lack of courage particularly when it comes to writing.

Is there any writer in the world who has not spent a good deal of their time feeling this way? You have this idea, starting out, of the books you will write, and no matter where life takes you, you will always feel that you have not quite accomplished what you set out to. When Ernaux wrote this journal, she was already a celebrated writer in France, and yet she still struggled with this fear of not being quite good enough.

On February 4th, just 30 pages into Getting Lost, Ernaux writes

A new notebook. Wishes…to write (as I yearn to do) a bigger, more sweeping book, starting at the beginning of ‘89…

That, she has done.

Get the book, Getting Lost, at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

As we head into the holiday week, wishing you joy and many good books!

-Michelle Richmond, Publisher / Fiction Attic Press

A longer version of this post originally appeared on my author newsletter.